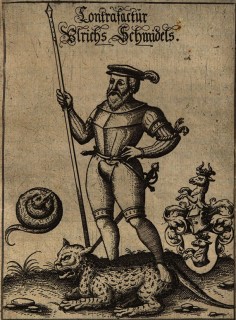

For example, a certain Ulrich Schmidel from Straubing was in the service of the conquistadors in South America between 1534 and 1554 and helped to enforce Spanish interests. In the process, he came into contact with the indigenous people living along the Paraguay River. The enterprising Schmidel traded knives, paternosters (rosaries), shears and other goods from Nuremberg for gold.

Also cylindrical tubes made of sheet brass were deposited in the graves of high-ranking persons of the Cuban society in the cemetery of El Chorro de Maíta, which was used from the 11th to the 16th century. They come from nesting tips from Europe and were most likely made in Nuremberg.

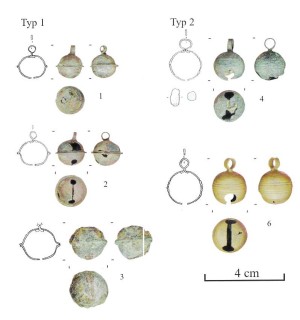

Nuremberg Bells in the New World

Nuremberg craftsmen produced goods of excellent quality and the city's merchants traded not only with neighboring regions, but also with faraway countries. Goods were already shipped to the - at that time still brand new - "New World" via the Netherlands. One of the Nuremberg products enjoyed great popularity worldwide: the bells. In North America, specimens of these small bells from the 18th century have been found. Based on the maker's mark, they could be identified as products of the workshops of Jakob Christoph Zimmermann (+1679), Wolfgang Zimmermann (+1728) and Johann Wilhelm Taucher (+1814) from Nuremberg.

Sources/literature:

Schmidel 1602, S.55 -> U. Schmidel, Vierte Schiffart. Warhaftige Historien. Einer Wunderbaren Schiffart, welche Ulrich Schmidel von Straubing, von Anno 1534 biß Anno 1554, in Americam oder Neuwewelt, bay Brasilia vnd Rio della Plata gethan, Nürnberg 1602.

I. W Brown, Bells. In: J. P Brain, Tunica Treasure. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Harvard University 71 (Cambridge Mass. 1979). 197-205.

Patrick Cassitti, Nürnberger Waren - Herstellung, Handel und Konsum europäischer Buntmetallprodukte in Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit, in: Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters, Beiheft 27, Bonn 2021.

Mark Howell, The Impact of Sound on Colonization: Spanish, French and British Encounters with Native American Cultures, from Colonial Guatemala to Virginia, in: R.Eichmann, M. Howell, G. Lawson: Music and Politics in the Ancient World, Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Bd. 65.