WELCOME..

...to the blog of IN TERRA VERITAS, an archaeological excavation company focusing on northern Bavaria/Germany. In this category "English" we offer some selected articles about the history, excavations and archaeological finds of southern Germany, since the Stone Age until modern times for our English speaking readers. Have fun with it.

Margaretha Königerin lives a simple life in Michelau in Lower Franconia (Bavaria/Germany). Her husband had already died 11 years before. Then comes the night of June 16-17, 1617. Several men took her out of her house and searched her belongings for witchcraft tools or ointments. The widow, over 50 years old, is put on trial for witchcraft. She immediately admits to being in league with the devil. 17 days later, she probably dies an agonizing death by fire at the stake. Her ashes are scattered to the wind, so that on Judgment Day there will be no body left for resurrection.

The witch mania

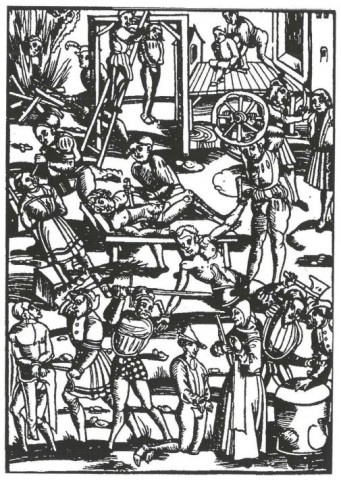

In the shadow of the climatic catastrophe caused by the Little Ice Age at the beginning of the 17th century and the beginning of the 30 Years War, a craze began in Central Europe that cost the lives of countless innocent people. Franconia was a sad center of this. In addition to the city of Bamberg, Gerolzhofen (district of Schweinfurt) was also a stronghold of witch hunts. 261 "witch people" were sentenced to death there by the Centgericht between 1616 and 1619. This number does not include those who died by torture or committed suicide in prison. In the first year alone, the Gerolzhofen judge Valentin Hausherr found 98 of 99 accused guilty and had them executed. Only one was acquitted. She was able to bribe the judge with two buckets of wine.

The trial of Margaretha Königerin

When in June 1617 the name of Margaretha Königerin from Michelau was mentioned during an interrogation of an unknown person, her fate was already sealed. The Halsgerichtsordnung (neck court) of Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn stipulates that if a person's name is mentioned several times during a witchcraft interrogation - usually from the 5th mention onwards - this person is also to be brought in on suspicion of witchcraft. Königerin is questioned on this by the judge Valentin Hausherr.

She willingly reports to have been introduced to witchcraft by Frau Stöcklein from Michelau, who was already executed in 1616. During the interrogation, she repeats details of the "Devil's Wedding" and the "Witches' Sabbath," which, however, were probably known to everyone at the time. When asked about the names of other participants in the coven, she mentions, among others, the wife of Eckhart Schmit from Dingolshausen. This is the 8th naming for Mrs. Schmit.

After this immediate confession, Königerin is imprisoned in Gerolzhofen. Her trial follows 17 days later, which is just a show. The judge and the jurors have already agreed on a verdict on the morning of the trial day. The trial itself will probably take place in the open air on the square in front of the city gate in Gerolzhofen.

Eight other people are found guilty with her that day and sentenced to death by burning. After the sentence is pronounced, there is a final confession and a last meal. After that, the condemned are taken to the place of execution. Here are already built stacks of wood, from which poles protrude to which the victims are tied.

Incidentally, the costs of the capture, interrogation, imprisonment, trial, the last meal and the wood for the stake, as well as the salary of the executioner and his assistants, had to be paid by the victim. The money usually came from the confiscation of all or most of the victim's property.Inevitable fate

The motivation to immediately admit to a crime that one obviously could not have committed is incomprehensible at first glance. But Margaretha Königerin knew that her fate was sealed. She saved herself hours or days of torture. Moreover, she named a person who had already been executed as her "witch teacher" and thus protected others. Perhaps she also named Mrs. Schmit from Dingolshausen only because she knew or assumed that she was already lost anyway.

And the fate of the judge

Valentin Hausherr was arrested on July 7, 1618 by men of the bishop. He was to be tried for corruption, drunkenness on duty, forgery of documents and other offenses. Hausherr hanged himself in his cell on November 28, 1618. His body was burned the next day. The ashes were scattered to the wind.

Sources:

Pfrang 1987:M.Pfrang, Der Prozess gegen die der Hexerei angeklagten Margaretha Königer, in: Würzburger Diözesangeschichtsblätter, Bd 49, Würzburg 1987, S. 155-167.

Jäger 2004:F.A. Jäger, Geschichte des Hexenbrennens in Franken (insbesondere Gerolzhofen) im 17.Jahrhunderts aus Original-Prozeßakten, Gerolzhofen 2004.

Bräutigam 2008:E.Bräutigam, Die Hexenverfolgung im Hochstift Würzburg, in: Frankenland – Zeitschrfit für fränkische Landeskunde und Kulturpflege, Bd. 60, Würzburg 2008, S. 4-14.