A royal funeral ceremony in England

The carriage

A special carriage was made ready for transporting the dead king. Its floor was padded with hay and covered with a black cloth. On it the coffin was placed, on which again a valuable cloth was spread. And on top of this was a picture of Christ as judge. The carriage was decorated front and back with two large candles and three banners with representations of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary and St. George. It was drawn by four horses, each of which was led by a groom and ridden by a page dressed in a black frock. The horses themselves each bore a saddlecloth with images of St. George, St. Edward the Confessor, St. Edmund the Martyr, the personal coat of arms of Henry V, and the coats of arms of England and France.

The funeral procession

The actual funeral procession was preceded by subjects in black robes with torches. Henry V's funeral procession was led by leading officials of the court. Behind them walked several clergymen of different ranks, including the confessor and court chaplain of the deceased. This was followed by several knights and lords on horseback. Behind them rode an Earl in full armor but without a helmet and armed with a battle axe pointed downward. His horse was decorated in the colours of Henry V. This knight symbolized the dead king, who was followed by other knights dressed in black with the royal coat of arms. Only then came the carriage with the coffin, accompanied by the main mourners. During the funeral procession in France, this was Katherine of Valois, the king's widow. On the English side of the Channel, this role was assumed by James I of Scotland.

On the route between the English coast and London, the procession made several overnight stops at the most important churches. Each time, an elaborate shrine was erected, decorated with black cloth and numerous candles.

The ceremony in London

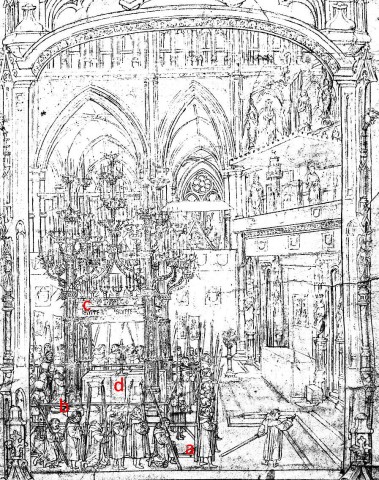

For the arrival, the streets of the capital were cleaned and decorated. The mayor and members of the city council, accompanied by 300 torchbearers dressed in white robes received the funeral procession. The coffin was laid out overnight in St. Paul's Cathedral and the following day taken through streets lined with spectators to Westminster Abbey. There, the funeral service lasted another two days.

The coffin was laid here in a specially made shrine in front of the main altar. It was surrounded by wooden barriers, which were wrapped in black fabric. The barriers served to separate important and less important participants of the funeral service. The clergy sat in the choir stalls. Mass was said by the archbishop, who also waved the thurible. All the guests were dressed in black velvet. After the service, they were allowed to retire for dinner. Through the night there was a guard of honour made up of changing members of the court.

The following day, three masses were said, during which the mourners made offerings in the form of cloth interwoven with gold. Westminster Abbey thus received 222 "golden cloths", 40 of which were resold and the rest added to the monastery treasury. The burial itself took place at the last of the three masses. During the requiem for the last mass, a knight came to the altar on the king's horse and in the king's armor. This was symbolically to offer the horse and the military successes as a sacrifice.

After the burial, a second knight in similar armor rode to the king's burial place and laid the royal escutcheon upside down at the dead man's feet. This ritual was to show that the king had died. Afterwards, a member of the royal family picked up the shield and laid it down again the right way around to show that the new king was alive and to indicate his successful succession. This symbolic act was performed even if the new king had not yet been crowned.

After the end of the funeral ceremonies, alms and food were distributed among the people.

Henry V's successor was his son Henry VI, who was just eight months old at the time. The kingdom was administered by deputy regents until he was 10 years old.

Literature:

Joel Burden, English Royal Funerals in the fifteenth century, in: J.R. Mulryne, European festival studies: 1450-1700, Trunhout, Belgium 2021. S.89-106